Last Updated : April 1, 2018

Introduction

In October 2017, members of the Canada's Drug Agency Patient Community Liaison Forum emphasized the need for patient voices to be heard by those involved in the Canada's Drug Agency governance, including the Canada's Drug Agency Board. Currently, the forum plays a role in sharing patient group concerns with Canada's Drug Agency and receiving broad overviews of activities being undertaken by Canada's Drug Agency. However, since the forum was created in 2013, expectations for greater engagement between patients and those responsible for health care planning and delivery (at individual, community, and population levels) have evolved.

For example, new Accreditation Canada standards require patient engagement in governance, leadership, and service delivery. Changes that have been integrated in the governance, leadership, and service excellence standards include: co‐design of services, client and family representatives on advisory and planning groups, and monitoring and evaluating with input from clients and families.1 Health Canada also describes public engagement as an important part of the democratic process to improve the understanding of issues and to facilitate opportunities between Health Canada and individuals, groups, and organizations, to help shape government policies and decisions.2

For example, new Accreditation Canada standards require patient engagement in governance, leadership, and service delivery. Changes that have been integrated in the governance, leadership, and service excellence standards include: co‐design of services, client and family representatives on advisory and planning groups, and monitoring and evaluating with input from clients and families.1 Health Canada also describes public engagement as an important part of the democratic process to improve the understanding of issues and to facilitate opportunities between Health Canada and individuals, groups, and organizations, to help shape government policies and decisions.2

To consider a future holistic approach to greater patient engagement, it was proposed that Canada's Drug Agency undertake a high-level environmental scan to look at different ways stakeholders can be embedded throughout an entire organization. The examples found can help Canada's Drug Agency and forum members co-design a new model for patient engagement that goes beyond the current form of consultation on operational matters.

Methods

A literature search was conducted to find published reports that describe examples of patient, public, or citizen involvement in organizational governance. Ovid MEDLINE, Scopus, and EBSCO Health Policy Reference were used, as well as a focused Internet search. The search was limited to English-language documents published between January 1, 2013 and March 12, 2018.

One reviewer (SB) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all citations retrieved from the literature search, and full texts of all potentially relevant reports were accessed for detailed review. Any uncertainty was resolved through discussion with a second reviewer (TR). We selected reports to provide a wide range of different approaches to stakeholder engagement in governance. When there was duplication of approaches, a report with greater detail on implementation was selected over those with limited information. A narrative synthesis of the reports follows.

Successful Engagement

Miller et al. identifies four organizational dimensions that contribute to success in patient engagement:3

- Governance ‒ a comprehensive, organization-wide policy acknowledgement of patients as key stakeholders; partnership roles based on mutual respect for one another’s different knowledge and experience decided through consultation between patients, the public, and researchers; and resources including a practice guide to support policy implementation

- Infrastructure ‒ lists of people willing to work; registers of patients with experience working in research, advocacy, and policy development

- Information ‒ formal and informal support networks, and resources and opportunities for patients and the public to share information and advice

- Capacity ‒ adequate support through training, education, and resources appropriate to the expected roles; researcher training to better understand the contributions the community can make to the research as active partners; as a research organization, actively promoting and advocating for greater patient participation in health and medical research.

Pagatpatan and Ward also identifies four mechanisms to achieve effective public engagement:4

- Political commitment ‒ a willingness by those in authority to listen, the dedication of appropriate resources to process, and the provision of a feedback loop on how input is used; these mechanisms work best when the identified health problem is specific, it affects the common good, and it is considered a priority for all participants

- Partnership synergy ‒ involves trust, a quality working relationship, and a sense of shared identity

- Inclusiveness ‒ requires a diversity of participants and recognition that varying degrees of public participation will happen; an altering of power dynamics and use of multiple approaches to ensure constant communication with the wider community

- Deliberativeness ‒ safeguards against internal exclusion; the use of a professional facilitator to ensure reasoned and informed discussion; and providing balanced, simplified, and relevant informational materials to use in deliberations.

From the UK, the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership recommends that patients and the public be involved at all levels of decision-making within National Health Service trusts.5 It offers these seven principles:

- Representation ‒ participants will be broadly representative of the relevant, affected population

- Inclusivity ‒ Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership will provide sufficient resources to overcome barriers such as issues of access or communication

- Early and continuous ‒ patients will be involved as early as possible and continue to be involved throughout; patients will also be involved in all areas of the Partnership’s work

- Transparency ‒ those involved will be able to see and understand how decisions are made

- Clarity of purpose ‒ the nature and scope of involvement will be defined prior to involvement

- Cost-effectiveness ‒ involvement must add value and be cost-effective

- Feedback ‒ the outcomes of patient public involvement activities will be fed back to participants.

Forms of Patient Involvement in Governance

Within the literature, three broad categories of governance were described: organizational decision-making, process design involving end-users (co-production), and policy-making. Within each category, different stakeholders may be involved, and involved at differing levels of engagement. Following an overview of each category, we describe examples of how different health organizations involve patients in their governance and, finally, explore the different dynamics that arise when patients or patient groups, or members of the public, are involved as stakeholders.

Organizational decision-making aims to integrate patients’ values, experiences, and perspectives into the design and governance of health care organizations. For example, patients may serve on hospitals’ patient and family advisory councils; participate in the design and execution of quality improvement projects; and assist with staff hiring, training, and development. 6 Collaborative methods may include patient advisory councils, expert patients, retreats, involvement on ethics committees, and in town hall meetings.7

Co-production of new processes and services can address power imbalances by designing and delivering public services in more democratic, equal, and reciprocal relationships between professionals, people using services, their families, and their communities. By introducing new roles, partnerships, and collaborative models, co-creation offers the opportunity to proactively engage patients and other stakeholders who typically have been marginalized within clinical settings.8

Six principles support co-production:

- Assets ‒ recognizing people as assets

- Capabilities ‒ building on people's existing strengths

- Mutuality ‒ reciprocal relations with mutual responsibilities and expectations

- Networks ‒ peer support, and engaging a range of networks inside and outside of health care services

- Blurring of roles ‒ removing tightly defined boundaries between professionals and recipients to enable shared control and responsibility

- Catalysts ‒ a shift from delivering services to supporting things to happen.9

Policy-making involves patients collaborating with community leaders and policy-makers to solve social problems, shape health care policy, and set priorities for the use of resources. Patients also participate in health and clinical research. At this level, engagement may include individual patients, as well as representatives of consumer organizations who speak on behalf of a general constituency.6 Organizational empowerment methods include a citizen jury, consumer-managed services, citizen panels, deliberative polling, think tanks, and consensus conferences.7

Examples of Patient Involvement in Organizational Decision-Making

European Medicines Agency

Advisory Capacity

Management Board: This includes two members representing patients’ organizations (the European Consumer Organisation and EURORDIS‒Rare Diseases). This group has a general responsibility for budgetary and planning matters, the appointment of the Executive Director, and the monitoring of the Agency’s performance.

Scientific Committees: There are six scientific committees for human medicines at the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and patients are full voting members of four of these. Activities performed by patients’ representatives in these committees include orphan designation of medicinal products, assessment of pediatric investigation plans, classification of advanced therapies, and assessment and monitoring of safety issues of medicines. Patients represent their organization.

Patients and Consumers Working Party: This is an important platform for exchange between the Agency and patients’ and consumers’ organizations. This working party collaborates and holds common meetings with the Healthcare Professionals’ Working Party, and is further divided into topic groups to promote further discussion on specific topics and provide opportunities for members of other eligible organizations to join. Topics include measuring the impact of patient involvement in EMA activities, acknowledging and promoting the visibility of patient input into the Agency’s activities, training and supporting patients involved in EMA activities and involving young people in EMA activities, and social media.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research

Rationale

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) values the engagement of citizens in governance, research priority setting, developing its strategic plans and strategic directions, and as an effective means of improving the relevance and translation of research into practice and policy.

Advisory Capacity

CIHR’s Framework for Citizen Engagement introduces an organizational strategy to build capacity within CIHR, within the public, and within the research community to increase the number of activities undertaken with greater patient and public engagement, such as memberships on standing committees and advisory boards. 10

Within the CIHR’s Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR), the SPOR National Steering Committee oversees SPOR development and implementation. Members include patients, federal/provincial/territorial governments, provincial health research funders, academic institutions, health care organizations, researchers, health charities, and industry. 11

Each SUPPORT — Support for People and Patient-Oriented Research and Trials — Unit will develop and implement a patient engagement plan, which includes patient participation in governance and decision-making processes. SUPPORT Units will also track and report on results of patient engagement activities in their jurisdictions. SPOR research networks will create a process for patients, citizens, and community stakeholders to be actively involved in research governance and participate in the research itself.10

Ontario Hospital Patient and Family Advisory Councils

Rationale

In 2010, the Excellent Care for All Act became law, with the mandate of putting Ontario’s patients first by strengthening the health care sector’s organizational focus and accountability.

Advisory Capacity

These advisory councils serve as forums for patients and families to participate as advisors and partners in shaping and making changes to improve the patient and family experience within hospitals, across catchment areas and, for specific populations, across the system. The Patient and Family Advisory Council (PFAC) can be partnered with the hospital, or it can operate independently. Participants share their unique experience-informed perspectives and advise on issues and decisions that impact the delivery of health care and the quality of experience for the next patient or family member.

Hospitals with more established PFACs tend to have a general advisory body embedded within the organization, as well as multiple smaller program- and project-specific or community-focused councils and integrated individual advisors throughout their organizations. The more experienced councils tend to work on corporate and policy issues — sitting on staff interview panels, redesigning clinical and educational programs, revamping hospital policies. Several patient and family members have presented to hospital boards and earned endorsements for PFAC ideas and initiatives. Institutions with a PFAC, together with individual advisors and patient-experience partners (PEPs), were able to influence institutional policies and procedures at all levels of the organization – they had more personnel and therefore could participate in almost every aspect of hospital operations.12

Participants identified key operating practices to help make the PFAC more effective and efficient: administrative support, executive-level leadership, strategic recruitment and screening, and connection to clinical staff. Transparency was a key factor in building trust and a sense of confidence that the hospital and council were working toward the same goal. Management demonstrated transparency through concrete actions: providing feedback to members on issues being dealt with and responding to council requests for information.

Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux de la Mauricie-et-du-Centre-du-Québec

Rationale

CIUSSS Centre recruits, trains, and coaches patient advisors to participate in decision-making at the various levels of governance.

Advisory Capacity

CIUSSS constitutes a pool of 30 patient advisors who reviewed documentation, participated in process improvement activities and committees, and helped train students in health sciences.13

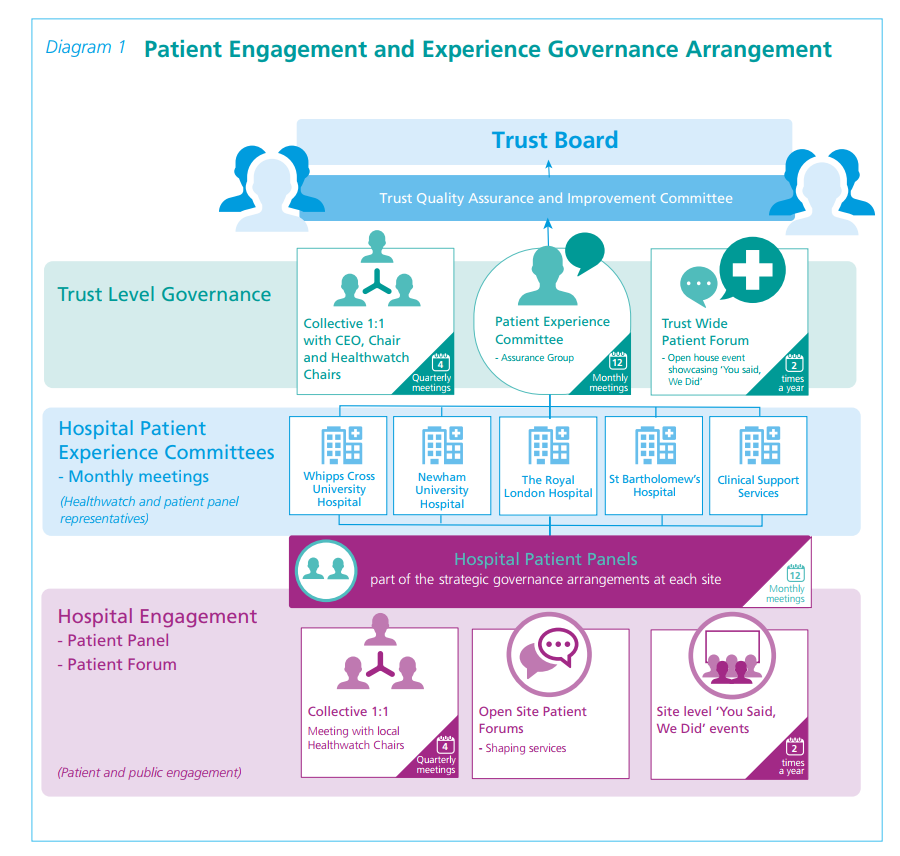

Barts Health, National Health Servise Trust (UK)

Rationale

Barts Health is the largest National Health Service trust in England and one of the leading health care providers in the UK. Barts Health wants the voice of patients, carers, the public, and voluntary and community sector partners to be heard in all parts of the organisation, from the recruitment and training of staff, to being the driving force of service design and assessing the quality of care.

Advisory Capacity

Kelly D. and Lloyd Knight, P. Patient Engagement and Experience Strategy, BARTS Health NHS Trust, 2016. Available at: https://www.bartshealth.nhs.uk/download.cfm?doc=docm93jijm4n5393.pdf

© BARTS Health NHS Trust, UK, 2016. This infographic is licensed under the Open Government Licence 3.0.

Community Health Centers (US)

Rationale

The intent of consumer-majority governance is to ensure the strategic influence for those served. Many assert, therefore, that consumer trustees make Community Health Centers more responsive to the needs of their communities.

Advisory Capacity

The Special Health Revenue Sharing Act of 1975 required US Community Health Centers to have a consumer-majority governing Board. This meant that at least 51% of trustees must be community health centre patients.14

Challenges of consumer governance include dominance by social elites, low levels of consumer participation, disparities in working knowledge between consumers and non-consumers, and unanswered questions about the effect of consumer governance on organizational outcomes.14 As a result, in many US Community Health Centers, consumer trustees are prized for their individual experience but not their representative role — which, ironically, was actually fulfilled by the professional staff because of their regular contacts with patients.14

Wright and Martin argue that a better way to achieve influence is to disregard consumers’ representative functions and draw on their personal motivations to instill public interest values within the organizational conscience and hold executives to account against social values.14

Examples of Patient Involvement in Co-Design

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (US)

Rationale

A broad range of communities have a stake in the effectiveness of our health care system. In the term “patient partners,” we include patients who are representative of the population of interest in a particular study, as well as their family members, caregivers, and the organizations that represent them.

Advisory Capacity

The Institute’s Advisory Panel on Patient Engagement helps refine and prioritize research questions, provides needed scientific and technical expertise, and models full and meaningful patient and stakeholder engagement efforts. With the Advisory Panel, the Institute developed a patient and family engagement rubric and a compensation framework on how best to compensate patient partners serving on research teams.15

The Patient and Community Engagement Research Program

Rationale

The Patient and Community Engagement Research (PaCER) program is working toward the following goals:

- reframing the role of “patient” to become a key stakeholder, partner, or colleague in health and health care

- promoting engagement in personal health and health care

- improving the interface between patients and the health care system through engaged research

- creating public and health-related venues for a collective patient research voice.

Advisory Capacity

PaCER Innovates is a research unit within the University of Calgary that generates revenue to conduct patient-led research. Through independent agreements with researchers and health providers, PaCER conducts research co-designed with patients, signalling new direction and challenging ideas based on patient input.

Examples of Patient Involvement in Policy-Making

Health Quality Ontario: Patient, Family and Public Advisors Council

Rationale

The Council ensures that Health Quality Ontario’s work and strategic priorities are guided by the lived experiences of Ontarians.

Advisory Capacity

Made up of 24 individuals from across Ontario, the Council’s members bring unique and diverse perspectives to the table based on their experiences with the health system. Individuals serve a three-year term and come together four to six times a year to share their advice and insights into what quality health care looks like. Topics discussed include transitions in care, long-term care, and advancing best practices for patient and public engagement across Ontario.

McMaster University Health Forum Citizen Panels

Rationale

The panels provide stakeholders access to public values, relevant to the topic under consideration, that have been systematically and transparently gathered and articulated.

Advisory Capacity

Citizen panels are held in advance of wider stakeholder dialogue. Key messages from the panels are included in the evidence briefs that inform the dialogue. Panels are composed of 14 to 16 citizens with varied lived experiences with the issues at hand, with participants selected to ensure ethnocultural, socioeconomic, gender, and other forms of diversity. The panels deliberate about a problem and its causes, the options to address it, and key implementation considerations.

Example topics include enhancing equitable access to assistive technologies in Canada, making fair and sustainable decisions about funding for cancer drugs in Canada, enhancing access to patient-centred primary care in Ontario, defining the mental health and addictions “basket of core services” to be publicly funded in Ontario.

Boivin et al. found that a combination of small-group deliberations, wider public consultation, and a moderation style focused on effective group process helps level out the power differences between professionals and the public.16

Institute of Health Economics Layperson Advisory Committee

Rationale

The Layperson Advisory Committee reflects on Institute of Health Economics (IHE) research activities and priorities, and provides feedback and ideas about how to improve IHE products and programs.

Advisory Capacity

The Committee involves eight members, including the Chair. Members have no direct connection with IHE programs and are diverse with respect to age, gender, occupation, and ethnic and political background. The Committee meets twice a year; each meeting includes an informal dinner and a six-hour meeting the next day. A senior IHE manager, in collaboration with the Chair, prepares for the meetings in advance, and agendas, including documents for discussions, are distributed by email in advance of the meeting. The meetings include information about programs and research activities at IHE. At the end of each meeting, participants prepare and share with the IHE management team a report that highlights the Committee’s feedback and suggestions resulting from their discussions. Participants receive an honorarium and compensation for their travel and accommodation expenses.17

Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Ontario Citizens’ Council

Rationale

The Council provides a mechanism for citizens of Ontario to provide input into drug policies and priorities in response to the 2006 Transparent Drug System for Patients Act.18

Advisory Capacity

The Council is made up of 25 members appointed by the Minister through the Public Appointments Secretariat following a recruitment process established by an independent advisory body. Membership terms are three years, with one-third of the Council retiring each year. To be eligible for membership, individuals must be older than 18, a resident of Ontario, and cannot be a health care professional, a paid employee of a health charity, employee of a company in health industries, an elected official, or an employee of the Ministry.

The Council meets twice a year, for two to three days at a time. A typical Council meeting begins on Friday evening and runs for two full-day sessions on Saturday and Sunday. Members are advised of the meeting dates, location, and topics to be discussed at least two months in advance. New members receive orientation on the process prior to their first official meeting.

After each meeting, a report is developed to serve as formal input into policies in development by the ministry. Examples of topics include drugs for rare diseases (2018), prescriber responsibilities (2017), and the development of a new drug program (2016). The reports are available online, and parts of the Council meetings are open to the public for those who have registered prior to the meeting.18

Example of Patient Involvement in Organizational Decision-Making and Policy-Making

NICE‒National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Citizens Council (UK)

Rationale

The Institute and its advisory bodies are well-qualified to make scientific judgments but have no special legitimacy to impose their own social values on the National Health Service (NHS) and its patients. These social values, NICE believes, should broadly reflect the values of the population who both use the service (as patients) and who ultimately provide it (as taxpayers). NICE has therefore established a Citizens Council, drawn from the population of England and Wales, to help provide advice about the social values that should underpin the Institute’s guidance.

Advisory Capacity

The NICE Board involves patient and public representatives. Six Board meetings are held each year. They are open to the public and conducted in different locations across the country. The full agenda, minutes, and discussion papers are shared publicly.

The NICE Citizens Council advises the Board on ethical issues and society’s views. The Council is a panel of 30 members of the public who largely reflect the demographic characteristics of the UK. Councillors are recruited by an independent organization and serve for up to three years. Members meet once a year for two days at a time and their discussions are arranged and run by independent facilitators. The meetings are open to public observers. During the meetings, Council members listen to different views from experts on a topic and undertake exercises that allow them to examine the issues in detail and thoroughly discuss their own views. The Council wrestles with questions such as:

- what are the societal values that need to be considered when making decisions about trade-offs between equity and efficiency?

- in what circumstances should NICE recommend interventions where the cost per quality-adjusted life-year is above the threshold range of £20,000 to £30,000?

- is there a preference to save the lives of people in imminent danger of dying?

Patients Involved in NICE, or PIN, is an independent group of patient organizations aiming to ensure that NICE decision-making is centred on the patients and their families.

Who to Involve?

As clients and service users, patients and patient’s families are the ideal partners for involvement in the organizational governance of regional hospitals and health centres. An understanding of the motivation and expectations of participants is important, as well as the barriers to volunteering, especially at decision-making levels where immediate personal (health) gain is harder to identify.19 Minorities are often under-represented in spaces created to give patients voice in governance. Lack of awareness of opportunities for participation, insufficient mobilization efforts, lack of resources, and mismatches between users' aims and the aims favoured by the organizations undermine their involvement. Excluding minority groups from the health participatory sphere may weaken the transformative potential of public participation, (re)producing health inequities.20

For organizations with a provincial, national, or multinational mandate, who to involve as patient partners is less clear. Patients are not only users and consumers of medical services, they are also citizens and taxpayers, and their collective well-being may be enhanced if their voices are considered in the system design for the benefit of all.19 If the goal is increasing democratic input, government accountability, and policy effectiveness, stakeholders would include those directly affected (patients, families, patient groups) and those indirectly affected (taxpayers, members of the public). How can their participation as partners be done with an effective use of resources?

Patient group representatives are established leaders in their communities and have unique knowledge about their community needs. This representation in organizational governance is an important way vulnerable groups are represented and a key element of advocacy involvement in many non-profit organizations.21

To gain the most from patient group involvement, Mosley suggests the following:

- Invite groups that have a demonstrated commitment to democratic principles in their own organization including ongoing outreach and communication strategies, establishing participatory mechanisms within their own organizations, and soliciting members’ feedback.

- A variety of patient group participants should be chosen to participate. Communities are diverse and the organizations that represent them should be, too.

- Groups that participate should return information to their members and involve membership in participatory forums directly.

- Evaluation and innovation is needed to avoid the process becoming primarily ceremonial. For example, the growth of social media technology is an alternative way to get participation and feedback directly from patients, and does not require a burdensome time commitment.21

Additionally, Rojatz and Forster recommend that, to support their positions as patient representatives, to gain acceptance, and to prevent overload, patient groups need resources which should be provided through public health policy.22

References

- Engagement toolkit. Charlottetown (PE): Health PEI; 2016: http://www.gov.pe.ca/photos/original/hpei_engagetool.pdf. Accessed 2018 Mar 13.

- Health Canada. Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada guidelines on public engagement. Ottawa (ON): Health Canada; 2016: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/healthy-canadians/migration/publications/health-system-systeme-sante/guidelines-public-engagement-publique-lignes-directrice/alt/pub-eng.pdf. Accessed 2018 Mar 13.

- Miller CL, Mott K, Cousins M, et al. Integrating consumer engagement in health and medical research - an Australian framework. Health Res Policy Syst. 2017;15(1 ).

- Pagatpatan CP, Ward PR. Understanding the factors that make public participation effective in health policy and planning: a realist synthesis. Aust J Prim Health. 2017;23(6):516-530.

- Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership. Involving patients. 2018; https://www.hqip.org.uk/involving-patients/. Accessed 2018 Mar 13.

- Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):223-231.

- Kovacs Burns K, Bellows M, Eigenseher C, Gallivan J. 'Practical' resources to support patient and family engagement in healthcare decisions: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:175.

- Singh G, Owens J, Cribb A. What are the professional, political, and ethical challenges of co-creating health care systems? AMA J Ethics. 2017;19(11):1132-1138.

- Ocloo J, Matthews R. From tokenism to empowerment: progressing patient and public involvement in healthcare improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(8):626-632.

- Strategy for patient-oriented research - patient engagement framework. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Institutes of Health Research; 2014: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/spor_framework-en.pdf. Accessed 2018 Mar 13.

- Evaluation of the strategy for patient-oriented research. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Institutes of Health Research; 2016: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/evaluation_spor_2016-en.pdf. Accessed 2018 Mar 13.

- The Change Foundation. Patient/Family Advisory Councils in Ontario hospitals – at work, in play. 2018; http://www.changefoundation.ca/patient-family-advisory-council/. Accessed 2018 Mar 13.

- Pomey M-P, Morin E, Neault C, et al. Patient advisors: how to implement a process for involvement at all levels of governance in a healthcare organization. Patient Exp J. 2016;3(2):99-112.

- Wright B, Martin GP. Mission, margin, and the role of consumer governance in decision-making at community health centers. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014;25(2):930-947.

- Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Engagement in healthcare research. 2018; https://www.pcori.org/engagement. Accessed 2018 Mar 13.

- Boivin A, Lehoux P, Burgers J, Grol R. What are the key ingredients for effective public involvement in health care improvement and policy decisions? A randomized trial process evaluation. Milbank Q. 2014;92(2):319-350.

- Practices for implementing effective public advisory groups of lay people or members of the general public. Edmonton (AB): Institute of Health Economics; 2014: https://www.ihe.ca/download/practices_for_implementing_effective_public_advisory_groups_of_lay_people_or_members_of_the_general_public.pdf. Accessed 2018 Dec 7.

- Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Citizens’ Council 2018; http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/drugs/councils/ Accessed 2018 Dec 7.

- Rowley S, Rowley E. Igniting innovation: engaging patients and the public in service transformation (strategic level decision-making). Nottingham (GB) 2018 Dec 7 2015. SPreading Applied Research and Knowledge - Longer Evidence Review 5.

- de Freitas C, Martin G. Inclusive public participation in health: policy, practice and theoretical contributions to promote the involvement of marginalised groups in healthcare. Soc Sci Med. 2015;135:31-39.

- Mosley JE. Nonprofit organizations’ involvement in participatory processes: the need for democratic accountability. Nonprofit Policy Forum. 2015;7(1):77-83.

- Rojatz D, Forster R. Self-help organisations as patient representatives in health care and policy decision-making. Health Policy. 2017;121(10):1047-1052.

Last Updated : April 1, 2018